From 2018 to Today: How Streaming Got Worse While We Stayed Quiet

A few days ago Netflix removed one of the most basic, useful, and long-standing features of its platform: the ability to cast content from a mobile phone to the TV. The change arrived without warnings, press releases, or explanations—another small drop in a bucket that is getting harder to tolerate.

As of a few weeks ago, it is no longer possible to cast Netflix content from a mobile device to most televisions or Android TV devices. The company now encourages users to pick up the TV remote and use the built-in Netflix app instead, a solution nobody asked for. Several users say the restriction began around November 10 with no notice, although Netflix has quietly updated a support page to acknowledge that the feature has been removed.

The most striking thing isn’t just the disappearance of casting; it’s the fine print that comes with it. The feature will only remain available on third-generation (or older) Chromecasts that did not include a remote, and only for subscribers on ad-free plans. If you have compatible hardware but you’re on the ad-supported plan, the feature is blocked. The move is reminiscent of the 2019 removal of AirPlay support, justified at the time with a vague need to “ensure a standard of quality.” Today, that kind of corporate phrasing sounds emptier than ever.

But this specific removal is only a symptom of something bigger. Writer Cory Doctorow coined the term “enshittification” —now it's a book!—to describe the cycle many digital platforms go through: first they’re good to users to grow, then they start prioritizing commercial partners, and in the final stage they squeeze everyone to capture as much value as possible. Netflix fits that pattern almost perfectly.

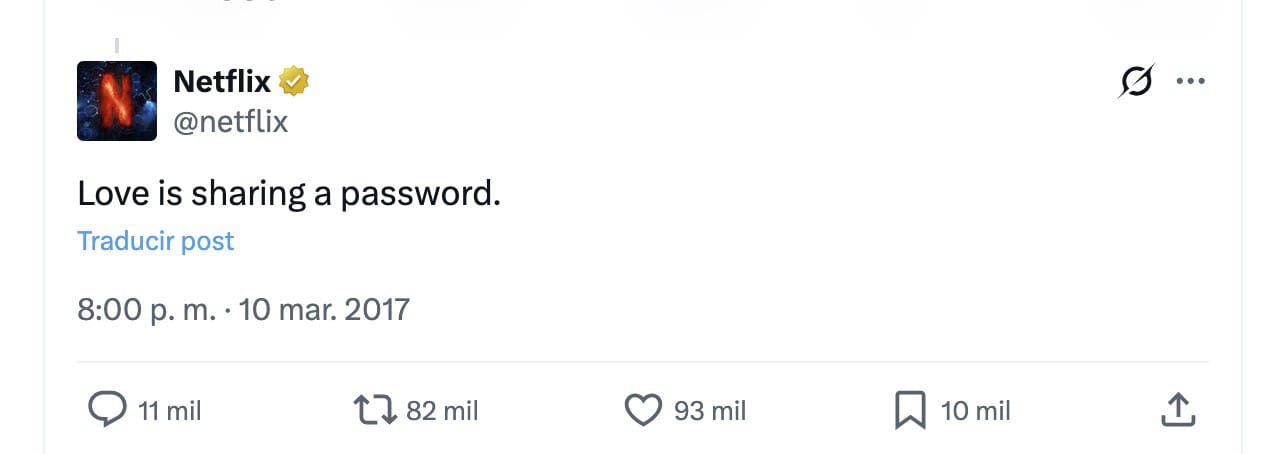

You only need to look back a few years. In 2018, Netflix was simpler, clearer, and more user-friendly. The interface wasn’t full of tricks to push its own content. The catalog wasn’t yet fragmented by the streaming wars. Casting worked universally. And, paradoxically, the company itself encouraged people on social media to share their passwords as a gesture of goodwill. That era is over: the crackdown on shared accounts made it clear that the old spirit of openness was gone.

The removal of casting reinforces the same idea. There are no strong technical reasons, no security concerns, no improvements to justify it. Netflix simply prefers that you use its TV interface—an environment it controls completely, where it can decide which content appears first, which banners you see, and how often. The convenience of using your phone as a remote no longer fits with its goal of maximizing visibility and advertising.

And Netflix is not alone. Amazon Prime Video has also embraced advertising, first cautiously and then with increasing intensity. What used to be a premium perk for Amazon Prime subscribers has become an advertising showcase, and to return to the original experience you must pay extra.

YouTube and Spotify are following similar paths. Both platforms have multiplied their ads and added more visual and auditory clutter. Spotify’s shift has been particularly intrusive: vertical videos, animated cards, invasive recommendations. Functional simplicity has been sacrificed in favor of engagement at all costs.

What’s worrying isn’t only that companies are stretching the subscription model beyond recognition; it’s how passive we’ve become as users. We’ve normalized the loss of basic functions, the appearance of ads where there were none, and the constant degradation of an experience we’re supposedly paying to improve. When Netflix banned password sharing in 2022, many users complained loudly and threatened to leave. Some did, but not for long: today the platform boasts more subscribers than ever.

This collective passivity—the silent “better than nothing” acceptance—is what allows these changes to happen without resistance. After years of small penalties, restrictions, and removals, we’ve become used to simply being grateful that the service works at all, even if it works worse than before. Enshittification continues because no one stops it, and because we’ve internalized the idea that protesting is useless. Yet every small concession fuels a trend that is already starting to feel irreversible.